30 November 2005

The London Syndrome

The ridiculous pub closing laws did have a rationale when they were put into effect: up until the First World War, English drinking establishments opened and closed (if they closed at all) when they felt like it and/or according to the number of customers on the premises, much as it's done in many other European countries. But, worried that hungover workers would blow themselves and the bomb factories to smithereens, the government instituted draconian restrictions on drinking times in 1914. Given the ponderous English inertia which stubbornly resists any change whatsoever to "tradition" (even if said tradition was only recently invented), it's rather startling that any politician dared come out in favour of liberalising licensing hours.

True, people have been moaning about the present system ever since it was put into place, but one thing not always understood is the distinction between English moaning and American complaining. "You Americans complain about things with the expectation of changing them," my friend Danny explains. "Englishmen don't bother complaining, because they know in their hearts nothing will come of it. So they moan. In fact, I rather think they prefer it that way."

Nevertheless, Labour campaigned and won election in 1997 on a promise to extend closing times for pubs, and did so again in 2001. Of course they never actually did anything about it, apart from a continual promise that it would happen "soon." And lo and behold, once they'd won a third term in 2005, it actually did. Americans need to understand that this represents breathtaking speed. If it were something more complicated, like completing the transition from imperial measurements to metric that began in 1965, it might take a little longer. Like 40 years, maybe? Oh, wait, that still hasn't quite happened…

Anyway, the law went through Parliament this year, despite a deafening chorus of opposition from the media, the churches, and the Tories, all predicting that allowing Englishmen to drink after 11 pm would rend asunder the last few threads of the social fabric and see the land awash in drunkenness, debauchery, and wholesale barbarism. If anyone dared ask how it was possible for less civilised people like the French or, God help us, the Americans, to drink far past midnight without a similar fate befalling their countries, they would be sniffily reminded that, "The English have a different sort of drinking culture."

If you've ever seen the vomitous and violent mobs that come swirling en masse out of pubs at closing time, you'd be forgiven for thinking so. But, the theory went, perhaps drinkers wouldn't be so surly if they weren't summarily tossed out into the chilly streets at an hour when they'd only just settled in for a pleasant night of boozing and conversation. And if they didn't feel compelled to slam dunk several pints in the last few minutes before closing time.

All the objections notwithstanding, the new law went into effect on the 24th of November. As someone who'd been complaining - American style - about this for years, I was deeply chagrined by a) being out of the country at the time; and b) no longer being a drinker.

But even though I haven't had a drink in some years, I enthusiastically supported the change, partly because I still enjoy going to pubs, and even more because I hoped that when pubs began staying open later, restaurants, shops and cafés would follow suit, and London might finally have a night life to at least rival that of Omaha or Salt Lake City. So on the 26th, my first night back, I eagerly headed down to Soho to witness the dramatic change.

Result: more or less nil. There might have been marginally more people milling around the streets, and of course the long-established after-hours clubs (most of which charge admission and double prices on drinks) were doing their usual business, but as for the regular pubs? All but a handful dutifully closed their doors at 11 pm, as if nothing at all had changed. It was as if you'd let someone out of prison and, not knowing what to do with himself, he came straight back and asked if he could keep on sleeping in his old cell. All but one of my favourite cafés were similarly shut up tight as a drum long before the witching hour.

Ah well, perhaps these things take time, as someone once sung. I note that the pub next door has taken the daring step of extending its closing time an entire half hour, to 11:30 pm. Perhaps by mid-century, they'll be open until 1 or even 2. Of course we'd then have to take up the issue of how everyone was supposed to get home: the Underground, its own hours closely geared to those of theatres and pubs, shuts down shortly after midnight (11 on Sundays). There seems to be an inbuilt suspicion that anyone out and about after that time is up to no good and certainly can't be trusted to ride on our lovely public transport system.

On the plus side (unless you are a leader writer for the Daily Mail), none of the predicted riotous behaviour has come to pass. Apparently Englishmen, provided they were sober enough to find one of the few pubs willing to stay open, have shown themselves capable of drinking themselves blotto at all hours without the Kingdom falling into rack and ruin. Who woulda thunk it?

Mendocino Homeland

It was only a little over a year ago that I sold the old Iron Peak homestead and left for the last time. I hadn't actually lived there since 1990, but couldn't bear to let go of it. When I was still in Berkeley, it provided a welcome respite: three hours on Highway 101 another half hour crawling the nine miles up Spy Rock Road, and I could relax in my own private wilderness.

But once I moved to England, the commute grew a little too arduous. When I did visit California, I was more inclined to spend time with friends and family than sitting by myself up on top of a mountain. Eventually I was only getting back to the old house for a few days a year, just long enough to get depressed about how it was slowly falling apart.

Wood houses will do that if they're not looked after, especially when an average year subjects them to searing heat, near hurricane-force winds, 100+ inches of rain and three or four blizzards. When I lived there fulltime, I kept the place in more or less functional shape, even though I'm not exactly the handyman type. But once I was no longer there on a regular basis, small problems gradually become big problems, and it finally became a bit overwhelming. When the temperature dropped into single digits (I'm talking Fahrenheit here), the pipes froze. I'd repaired the plumbing many times before, but I didn't know how to get at the pipes inside the walls, so that was the end of the bathtub and shower. When the bear smashed its way into the house through the kitchen window, it not only broke the glass, which I could have replaced, but shattered the frame, which was a bit beyond my capabilities. The outside paneling, subjected to relentless morning sun because I'd foolishly cut down a tree that once shaded it, buckled and fell off. I’d nail it back, but what it really needed was replacing, again beyond my limited capabilities.

It's not that I'm completely helpless. I put in a water system that involved erecting tanks atop hills and running a pipe up and down cliffs for nearly half a mile. I developed and maintained a solar power system sufficient to power not just normal household appliances but also a whole punk rock band. I cut and hauled my own firewood, cleared culverts and reditched the road so that it didn't wash away in one of our 30-day downpours. But I'm pretty useless when it comes to carpentry, and that's what the place needed most of all.

"Why don't you just hire somebody to do the work for you?" city people would ask.

"It's not that simple," I would try to explain. "Nobody wants to do that kind of work. It doesn't pay enough."

"What are you talking about? Carpenters make really good money."

"It doesn't matter. No matter how much you're willing to pay them, the dope growers can always pay them more."

Once, only once, I was able to find someone to do some basic repairs and maintenance to the outside of the house. And he was doing a good job for about a week. Then one of the growers down the road let it be known that he needed help. My guy walked off the job, leaving one wall half done, never to return.

Many carpenters, electricians and plumbers end up growing marijuana instead, while those who continue to practise their trade work at building and maintaining the infrastructure for other growers. When the government started regular air surveillance and helicopter raids in the 80s, the biggest growers went underground - literally. They carved out house-sized chambers underneath their existing houses or outbuildings, installed massive generators to power their grow lights, and began producing marijuana all year round. A well-run operation could easily generate a million bucks annually.

With that kind of money floating around the once hardscrabble hills (after the Indians were driven off in the 19th century, they mostly sat fallow until the hippies started moving in during the 70s), nothing resembling a normal economy would ever be possible. Willits, Laytonville, Garberville, once sleepy aggregations of gas stations and truck stops, turned into boom towns. Government crackdowns accomplished nothing except to drive the price of marijuana ever higher, which attracted a new cast of characters, more hard driving and aggressive than the mom-and-pop hippie growers who'd pioneered the new agriculture.

By the time I left the mountain, most of the families were gone, replaced by high-powered commercial operations. Paranoia hung thickly over the otherwise spectacularly beautiful peaks and canyons, and a shroud of secrecy descended over what had been an open and friendly community. As long as I stayed on my own land, it was easy to imagine that things hadn't changed that much, but the steady hum of diesel generators and the cokeheads up the hill who liked to greet the dawn with bursts of their AK-47 told me otherwise.

That was when dope was still thoroughly illegal and the prices were sky high. Today, it’s semi-legal in California, thanks to Proposition 215, a ballot measure that allowed growers and dealers to claim that their marijuana was for “medical” purposes. Although there is a case to be made for medical pot, this particular law might as well have been written by drug dealers – actually it pretty much was – and any grower in Mendocino County who’s not too stoned to drive into town and buy a “prescription” from an obliging doctor is now a certified “medical provider.”

The result is that the price of dope has virtually halved since its high point in the late 80s/early 90s, which of course means that growers have had to double their crop sizes, but as long as they don’t exceed certain nebulous limits, the police are powerless to do anything about it. If the hippies were to be believed, this semi-legalisation should have led to a halcyon new world where gentle country folk lovingly grow their hemp “medicine” for grateful “patients” down in the cities, but in reality it’s merely institutionalised and brought partially aboveground a vast business making vast profits from people’s perennial desire to get high.

My most recent edition of the Anderson Valley Advertiser tells the story of the gangland-style execution of one Les Crane, a self-proclaimed reverend who ran a chain of marijuana dispensaries with names like Mendo Spiritual Remedies and Hemp Plus Ministry. Declaring dope a “sacrament” from the “tree of life,” Crane sounded like a refugee from the 1960s, but at 39, had barely been born when hippies (and I’ll freely admit I was one of them) started proclaiming this particular form of blather. Crane’s murder sounded especially brutal, with four or five black-clad and masked thugs charging into his house at 2:30 in the morning, but in retrospect, I guess it’s no worse than the time another grower was bludgeoned to death in a trailer just down the road from me. His assailant(s) then proceeded to set the forest on fire in an attempt to cover up the crime.

Hippies (and again, I was once one of them) insist that marijuana is a “love” drug, that it somehow makes people nicer and smarter and better behaved (or at least that’s how they see themselves when they’re stoned out of their gourds). They’ll argue that marijuana-related violence is not the fault of the drug itself, but rather stems from its illegality. But they’re overlooking the fact that marijuana affects different people in different ways. If you’re a gentle middle-class person who likes to reflect about philosophy, sure, marijuana might impel you to do more of the same. If, on the other hand, you’re a gang-banger who gets a kick out of seeing people bleed, well, you can just as easily trip on that.

My main objection to marijuana is that it dissolves – in some cases, I fear, permanently – people’s ability to think critically. In a pot-addled state, the most preposterous thought can enter the mind and be received as divine inspiration. You can and probably will end up believing just about anything, because when you’re stoned, your semi-functioning brain has become the absolute centre of the universe.

Oh well, I didn’t mean to go off on an anti-marijuana polemic (I’ve been working on one of those for a couple years, and it may soon see the light of day). I just wanted to give a wistful sigh for my beautiful Mendocino mountains, once home to a rich and diverse (if undeniably bizarre) culture, now increasingly the province of big agriculture and feral hippies.

29 November 2005

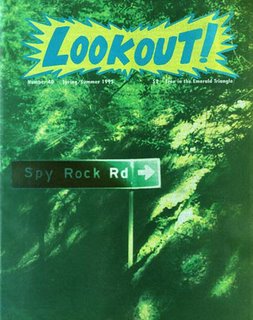

Lookout

No, this isn't about Lookout Records, so if you're looking for gossip on that subject, look elsewhere.

Several years before there was a Lookout Records, there was a Lookout magazine, which helped give birth to the band called the Lookouts, and in turn, eventually to the record label. But today I just wanted to write something about the magazine.

To apply the word "magazine" to four one-sided xeroxed pages might be stretching a point, but by the time Lookout stopped publishing (or at least went on a very long hiatus), it had grown to 64 newsprint pages and a circulation of nearly 10,000. The last full-length issue of Lookout was the slightly late 10th anniversary edition, published in early 1995. I never specifically decided to stop publishing it, but the intervals between issues had been getting longer and longer for a while, and this particular interval went on indefinitely.

Although I said this post wasn't about Lookout Records, the record label did play a part in both the rise and demise of Lookout magazine. For the first few years, Lookout came out more or less monthly, always in a xeroxed and stapled format, and distributed in the most basic way: I'd leave copies at bookshops, natural food stores, and similar hangouts, first in Mendocino and Humboldt Counties, and then later in Berkeley and San Francisco. It was free if you could find it, and a buck through the mail. If you're curious about how that worked (there was no paid advertising), it meant that for quite a while I ate the cost myself. It wasn't nearly as expensive as it could have been, because after I'd outgrown the primitive copying facilities Mendocino County possessed at the time (my first issue, all 50 copies of it, was run off at the feed store in Willits, with me personally feeding every page into the machine and stacking the finished pages on bags of manure in preparation for collating), I shifted operations to a large copy shop just off Berkeley's Telegraph Avenue. One day as I was sitting on the floor there, with thousands of pages stacked up all around, the manager came up to me. Oh oh, I thought, he's sick of me hanging around here all night and taking up half the floor space, but instead he said, "I been reading that thing of yours. You writin' some funny-ass shit there." With that he offered to copy and collate the Lookout at a tiny fraction of the normal cost. He gave us a similar deal on all the early 7" record covers we made once David Hayes and I co-founded Lookout Records in 1987.

In 1988, Lookout Records was offered a distribution deal by Mordam Records. This meant I was suddenly able to get the magazine into shops all over the country and a few spots in Europe. It also meant switching to a newsprint format and massively increasing the print run, but within a year or two Lookout magazine was paying its own way and even making a small profit. The downside was that Lookout Records' massive success completely dwarfed the magazine and left me with less and less time to work on it. It's no coincidence that it sort of petered out in 1995, the same year that the record label entered the multi-million dollar stratosphere thanks to sales of Green Day's back catalog. Lookout Records morphed from a happy-go-lucky crew of three clowns operating out of my bedroom on Berkeley Way into a full-fledged company with 14 employees and offices in downtown Berkeley, over which I was supposed to be maintaining some kind of charge.

Exhausted by it all, I left the record business in 1997, which meant that even if I'd found the energy or drive to restart Lookout magazine, I no longer had a distribution deal for it. Besides, everything was changing, and printed zines were either going bigtime or falling by the wayside. A few years into the new century, in the age of blogs and Myspace, it feels unimaginably archaic to think about launching or re-launching a print zine. Yes, I know there are people still doing it, and on my recent trip to the USA, I encountered several good ones, both new and old. But they just don't seem to have the impact or immediacy that they did in the 80s or 90s.

The first issue of Lookout, the four-page one, came out in October 1984. I printed 50 copies, and at least half of those were destroyed by irate readers. At the time I was living high atop Spy Rock Road in rural Mendocino County, an area populated almost entirely by marijuana growers, loggers, and a few random lunatics. The loggers were up in arms because of my environmental stance, the marijuana growers because they thought I was calling too much attention to our particular mountain. Hating me was one of the first things they'd ever had in common.

The loggers grumbled and wrote condemnatory letters about me to the local paper, the Laytonville Ledger, but the marijuana growers took more direct action. In the spring of 1985 a band of mean-looking hippies came marching up my driveway and told me that if I didn't stop publishing the Lookout, my house was likely to catch fire the next time I went to town.

I was at one of life's low ebbs at the time. My girlfriend of four years had just left me, I was so broke that I could barely afford to go town (perhaps the reason my house hadn't burned down yet), and putting together this little magazine was one of the few meaningful things I'd found to do with myself. I asked the hippies what exactly they objected to about the Lookout, and it basically came down to marijuana. My first issue had included a harvest report, citing crop sizes and the prices that local farmers were getting. As far as I could see, that was important news, since our mountain economy was almost entirely dependent on marijuana. Also, there wasn't a whole lot of other news; my other front page story had been about a bear breaking into somebody's house and helping itself to a feast of milk and cookies.

The other big objection was to the magazine's name: at that time it was called the Iron Peak Lookout, and featured a logo of the fire lookout tower atop the mountain that dominated our surroundings. "Thanks to you, the cops are going to know where to look for dope," my hippie neighbors complained. "But the San Francisco Chronicle had a huge story about dope growing on our mountain," I argued, "and the cops raid us every year. It's not exactly a secret that people grow marijuana here."

But they weren't in the mood for reason, especially not their leader, Tree Danny, a feisty little bearded man who'd gotten his nickname from cutting down trees on other people's property, and who hated me most of all for having made fun of the Grateful Dead. Teepee Doug, so named because, well, he lived in one, finally brokered a compromise: if I changed the name of the magazine to something not specific to the area, and if I didn't write about marijuana growing, I'd be allowed to live and my house probably wouldn't burn down.

So that's how the Iron Peak Lookout became the Lookout, and how its focus gradually changed from Spy Rock and Iron Peak minutiae to punk rock and regional and national politics. I still managed to get a lot of people mad at me; it's just that most of them no longer lived on the same mountain as me. In 1987, I had about half the town of Laytonville (population, 1,000) ready to kill me and the other half cheering me on as a dispute over a proposed asphalt plant escalated into a full-fledged culture war. Local characters supplied me with endless material, especially the likes of logging supplies baron Bill Bailey, whose campaign to remove Dr. Seuss's The Lorax from Laytonville schools for its alleged anti-logging bias ended up making national news. Although the Lookout by now had become the most widely read publication in northern Mendocino County, more and more of my readers were now from urban areas. To them, Laytonville and environs sounded like a cross between Hooterville, Hazzard County and Dogpatch: a broad, albeit hilarious caricature of rural life. "You mean all those people were real?" one of my big city readers asked me years later, "I thought for sure you had to be making that stuff up."

In 1990 I moved down to Berkeley to go back to college, and Lookout Records and Lookout magazine came with me. I still spent enough time up on Spy Rock to have plenty of gossip from the Emerald Triangle (the name given by law enforcement to Northern California's marijuana-producing region), but the focus continued to shift toward the Bay Area and the Gilman Street scene. I found that punks could get just as ornery as hippies if I failed to show sufficient respect for their favorite bands or pet political causes, but in their favor, at least they never threatened to burn my house down. By the time I'd graduated from Berkeley in 1992, running Lookout Records had become a full-time job, leaving me less and less time for the magazine. Despite this, I still insisted on personally writing almost every word myself, apart from the sometimes vitriolic, sometimes uproarious exchanges in the Letters to the Lookout pages. Using tiny 9-point type to take maximum advantage of the space available, I clocked up a book-length 50,000 words in a couple issues.

I guess burnout was inevitable, that and my increasing sense of isolation from the grass-roots punk scene as I became ever more entangled in the big business end of it. As much as I sometimes miss running a record label and running around the country to discover new bands, I think I miss writing and putting together the Lookout far more. Occasionally - very occasionally - someone encourages me to start the magazine up again, but usually it's an unreconstructed romantic like Aaron Cometbus, who's kept his own magazine going for close to 25 years now. Is Lookout ever likely to return? Probably not.

But I do have to say that writing for this blog - started, like Lookout, when I was at a low ebb in my personal and creative life - feels an awful lot like the days of xeroxing and stapling my first few issues, and I'm enjoying it in a way that I haven't experienced in years. Better yet, no one has threatened to burn down my computer.

At least not yet.

24 November 2005

Meet The Leftovers

All Night Laundry, North Solano

For those of you who don't know it, the song starts out, "All night restaurant, North Kildonan," and goes on to portray in exquisite detail the beauty and sadness of the solitude, shared or otherwise, that we sometimes seek out and sometimes stumble upon and is sometimes thrust upon us in those hours that hang suspended somewhere between midnight and dawn.

I've always tended to be somewhat of a solitude seeker. As a child, one of my recipes for happiness was to unearth some corner or cubbyhole where no one would ever find me and curl up with a comic book or a daydream. All these years later, the main thing that's changed is the nature of my hiding places. There's something to be said for out-of-the-way cafes or bars, and in nice weather there's always the park or the woods, but for full-on reflection, brooding or rumination the former can be too confining and the latter too unbounded. But one place that nearly always fits the bill is the all-night laundromat.

T.S. Eliot may have measured out his life in coffee spoons, but mine has been more about scoops of detergent. Some of my soul's darkest nights and some of my most blissfully contented hours have been whiled away in garishly lit laundrettes with only the gurgling of soap suds and the hypnotic clink-clank of coins trapped in the tumble dryer for company.

And tonight was just such a time. Tomorrow I'm off back to England and it occurred to me that some clean clothes might be useful. So just before midnight it was down to Solano Avenue, to the 24-hour laundromat I've been using since at least 1990 when I'm in Berkeley. In Berkeley itself, there's a deep-seated resistance to all-night establishments, presumably because they might require workers to keep unsocial hours. But just over the city line in Albany you'll find a 24-hour supermarket, doughnut shop and laundromat: pretty much all the prerequisites of civilization.

Tonight being Thanksgiving Eve, the street was even quieter than usual, and except for a couple random lunatics who wandered in and out again, I had the laundromat to myself. I read a chapter of Boswell's Tour To The Hebrides, with its amusing account of how Samuel Johnson's disinclination to "relinquish ... the felicity of a London life, which, to a man who can enjoy it with full intellectual relish, is apt to make existence in any narrower sphere seem insipid or irksome."

Then I stepped out into the street, and there was something in the air that felt more like rural Northern California than the Bay Area, that evoked memories of places like Laytonville and Fort Bragg and Willits and Eureka - in all of which I've had my late-night laundry moments. Years, hell, decades gone by, I thought, and here I am in the same Eternal Laundromat. Lines may form on my face and my hands, new clothes may cycle endlessly into the ragbag, only the laundromat stays the same. It was somehow depressing and comforting at the same time.

The laundry was done, but I wasn't ready for the night to be over. Train whistles came drifting up from West Berkeley the way they do on still East Bay nights, and it was time to wander. Somewhere along the way I hooked up with Aaron and we roamed through North Berkeley and Albany, much the same as we might have done after a Gilman show sometime last century, with a requisite stop at Winchell's Doughnuts (no longer known by that name, but old-timers will know whereof I speak). The booths were gone, replaced by little tables, but little else had changed, right down to the hooded man staring zombie-like at the endlessly repeating lottery numbers on the screen in the corner.

Then we walked again, and by now we'd exhausted all our political arguments and our news about friends and family and our speculations about what the future would bring; now there was nothing left but to revisit those streets, those feelings, those memories that we'd never dream of digging up in the light of day. "I was walking up this street in 1988 when I got this idea for a song," one of us would say, and the other would say, "No way, this is the street I was thinking of when I wrote that story," and then we'd go on to think about all the faces, all the places, all the people who've come, stayed a while, and spun off again into parts ethereal.

In another time and place, we probably would have walked till just before dawn, and then suddenly decided that we had to make a mad dash to the top of the hills before the sun rose. But neither of us is quite as crazy as we used to be, and about 3 am I retrieved my car from the laundromat and dropped Aaron off where he was staying. As I drove away, I turned on the radio. It was tuned to KALX, and a kid named Danarchy was talking about, "This thing I'm, um, going to play, it's like, um, from this compilation, it's like called The Thing That Ate Floyd, and it's all these early Lookout bands who used to play at 924 Gilman and stuff, and this track's by a band named Crimpshrine, it's called 'Summertime.'"

The music kicked in, the years fell away, and I thought about all those nights knocking around the streets, hanging out in doughnut shops, scratching down random thoughts and words and grabbing at melodies that flitted through our heads the way the winds off the Bay teased the treetops on the back streets of Berkeley. Who would have thought that it would add up to something a kid would be talking about on the radio in the 21st century as if it were important, as if it were history?

But there we were, and here we are, and for one tiny moment on one deserted street in Berkeley, everything was just about right.

23 November 2005

Someone...

20 November 2005

At Gilman Street

It's impossible for me to set foot in that place without some strong feelings washing over me, most of them overwhelmingly positive. So with that in mind, let's start with the negatives.

First complaint: Gilman Street itself, not the club, the street. When we opened the club back in 1986, part of the reason the City of Berkeley was willing to give us a permit was that it was in the middle of nowhere. Not much went on in West Berkeley in those days, especially at night, so you could pretty much hang out in the street and only occasionally risk being mown down by an aberrant driver.

No longer. Since the punks helped make West Berkeley ripe for gentrification, the City has had to put in a traffic light at 8th and Gilman, and despite that, it's still a tricky business getting across the street. Meaning I had to wait at least a minute and a half, which of course had me seething with indignation.

At the door I handed over my still-valid membership card and my $6 (another change; for most of its history Gilman subscribed religiously to the theory that charging more than $5 for a punk rock show was criminal blasphemy) and was on my way in when an older, bigger punk, who seemed to be acting as a sort of door supervisor, snatched my membership card away from the young girl who was taking the money and examined it carefully, as if he suspected me of forging it.

I've never found the "Do you know who I am?" card to produce anything but more trouble, usually seasoned with a soupçon of ridicule, so I didn't bother complaining that in October 1986 I had paid $2 for what was supposed to be a LIFETIME membership card, but which is no longer honored. To be fair to the suspicious doorman, I don't look much like a typical Gilmanite these days, but I wouldn't like to think I look like a membership card forger, either.

One last gripe, and it's actually the only one I'm serious about: I can't believe (well, yes I can; I was involved with the club long enough to believe almost anything) that they still allow smoking inside. It must be the last public space in California that does. I know the issue has been raised on occasion over the years, but my impression is that most of the punks are afraid to come out in favor of enforcing a smoking ban (it's been California state law for 7 years already) because it would make them look too authoritarian or parental. There still seems to be this misapprehension that there's something rebellious or edgy about giving yourself cancer. No drugs, booze, racism, sexism or homophobia is allowed at Gilman, but supporting the right-wing tobacco industry and fattening the coffers of corporate medicine and pharmacology? Hey, that's PUNK!

But by now I was inside, and the old surroundings worked their perennial magic on me. No matter how loud the music, how frenetic the activity, a kind of peace descends on my soul, a sense of coming home after a long trip and settling into a floppy old easy chair in the family rec room. Many of the kids in the audience weren't even born when Gilman first opened its doors, but they carry on the old traditions with ease and grace, flopping around on the sofas, alternately trying to look silly or surly and often succeeding in doing both at once, and in general having a great old adolescent time. Speaking of sofas, there's a pale blue denim one, now marked up with graffiti, that I swear used to be in my office at Lookout Records. How it could have migrated down the hill to Gilman Street might make for an interesting story one day, but all I could think about was all the hours I spent sleeping or otherwise goofing off on it when I was supposed to be transacting Important Punk Rock Record Business.

I got there in time to see only the last few songs by a young Oakland band called The Mothballs, whose picture may or may not appear somewhere on this page. Full of spunk and energy and attitude, they would have fit right into a Gilman show circa 1987 except that they were better dressed, a bit more skilled on their instruments, and probably weren't alive yet. Apparently they don't even have a record out yet (these days bands often have records out before they even play a show), but I suspect they will one day, and that it will be a very good one.

I found the famous Kendra K crawling around the floor of the sound booth, wiring up a live broadcast for Berkeley's own KALX, and snapped a picture of her which I'd put up here except that I'd prefer to live a little longer. Then I watched the Riff Randells, one of whom I'd met in Vancouver (where they're from) at (I think) the Mint Records anniversary party quite a few years ago. She must have been about 12 then, because the Riff Randells still look like schoolgirls, and rock out in a way the early Donnas might have done if the Donnas were... better.

From the rave reviews East Coast friends had given me, I expected the King Khan & BBQ Show to be some sort of 9-piece orchestra-type setup, but it turned out to be just two incredibly gifted guys, one of whom played guitar and drums and sang lead vocals all at once (that would be BBQ) and the other jumped around, broke guitar strings, howled and occasionally sang, and changed into drag in mid-set (that would be Khan). Mr. BBQ, while Khan was faffing about with his broken strings, sang and played a brilliant cover of "Out Of Time," an old Rolling Stones song I haven't heard in years, and later on in the set sang what might or might not have been a Sam Cooke cover in a voice which sounded so much like Sam Cooke that I didn't really care who actually wrote the song. Too bad my pictures of Mr. Khan in his silver dress and purple wig didn't come out too well, or you'd see them here. Or go see him in person. Highly recommended.

I didn't stay for much of the headliner Harold Ray Live, partly because I had to be up early for my 9 year old nephew's soccer match, partly because I've seen them several times before and found their jollity and kitsch slightly too forced for my taste. But as I drove up the hill, I listened to the broadcast on KALX and darned if they didn't sound vastly better than they ever did before. Either the band has hit a new groove, or Kendra's technical wizardry had catapulted them into the next dimension of excellence. Either way, I was kind of sorry I didn't stay, especially when I heard them doing this great song about outer space that may or may not have been a Phenomenauts cover (I was having a bit of difficulty following the stage patter). And my nephew's team ended up losing their game 4-0 anyway, so maybe I should have stayed up late last night and stayed in bed this morning. Maybe the whole team should have! They played like it, anyway! (Sorry, I get over-excited about soccer.)

Anyway, that's it for my Gilman report; I'm pleased to say that the place looks as great as ever and smells better (except for those accursed teenage smokers!). December 31st will mark the 19th anniversary of its first show ever, and who would have thought that anything put together by a bunch of goofy kids with funny hair could ever last 19 weeks, let alone years? Whatever little bit I might have done back in antediluvian times to help the Gilman Street Project get underway, well, it's repaid a thousand times over every time I come to town and walk through the doors of the World's Greatest Club Ever.

Friends In Need

Nonetheless, I bundled up my recalcitrant laptop and went to see Patrick Hynes, my onetime partner in both Lookout Records and the Potatomen. Patrick, in addition to being an inspired artist, one of the best musicians I've ever known, and an all-around great guy, also happens to be a computer genius. He plugged it in, waved his hands over it (or maybe just gave it an encouraging pat on the trackpad, I'm not sure) and of course it was instantly restored to good health.

The only trouble with asking Patrick for help of this kind is that I usually end up feeling pretty dumb for not knowing even the tiniest fraction of what he knows, but heck, I spend a fair amount of time feeling dumb for not knowing what lots of people know, so I can live with it. Anyway, I still needed Patrick to show me how to make an mp3 from a tape cassette, something I gather nearly everyone knows but me, but there you are again...

The mp3 I needed was of a song called "California." Actually, there are probably quite a few songs by that name, but this one was by late 70s SoCal band the Simpletones as covered by my old band, the Lookouts. The recent VH1 documentary Driven: Green Day used a snipet from the Lookouts version, and when Jay from the Simpletones got wind of it, he emailed me asking for a copy. He seemed thrilled that his old band's song had made it onto national TV, and I apologized for our amateurish butchering of it. At the time we recorded it in 1985, we'd only been a band for about six months, and our drummer, Tre Cool, who sings exquisite soprano backup vocals, was still just 12 years old.

Anyway, back in those ancient times, digital recording was virtually unheard of, especially for fledgling punk rock bands from the backwoods of Mendocino. The "master" copy of our 22 (!) song demo was a gnarly old cassette that had been kicking around in the dust somewhere up atop Spy Rock Road for many a year. A point of interest, possibly: the recording engineer on our demo was one Hal Wagenet, one-time guitarist for the hippie band It's A Beautiful Day and now a Mendocino County Supervisor.

So now a second Lookouts song has made it into the digital age; the only other one, which actually got remastered for CD, was "Outside," from the compilation The Thing That Ate Floyd compilation, written and sung by a 14-year-old Tre Cool. As for our Simpletones cover, for which we rewrote some lyrics to reflect our Mendocino version of the California experience (rather different from the Simpletones' SoCal one), it's now on its way to Jay, and as soon as I can figure out the technology, I'll set up a link so the rest of you can hear it. UPDATE: Patrick, ever the champion he is, has stepped in and provided me with just such a link: "California".

That's where the wonderful Kendra K comes in: she's been my adviser on all things bloggish, and please don't blame her because I'm a slow learner. I'm hoping she'll help me devise a way to make sound files available here, and while you're waiting, you can always head over to her neck of the woods and marvel at the aural fury that is Thee Kendrak Attack.

And seeing that I'm in slightly pluggish mode, I don't want to forget about Patrick and Erika's Little Type Mail Order, which to my mind is carrying on many of the best traditions of the old school Lookout Records. Not surprising, since Patrick was one of the main driving forces at Lookout from 1990 to 1997, and Erika applied an equally masterful (can you say that about a woman?) and adept hand to the Lookout mail order department. In addition to selling the kinds of records and fanzines that you might not find anywhere else, Pat and Erika are also now running websites and mail order for both Adeline Records and Screeching Weasel.

There's loads more to talk about, but right now I'm off for my semi-annual visit to Gilman Street. I'm especially stoked because for once my membership card from my last visit hasn't expired yet. Score two bucks for me!

16 November 2005

Berkeley In A Better Light

I knew it was him before he'd even knocked; I could tell from his familiar shuffle-and-clump coming up the stairs, and from the fact that almost nobody else knew I was here. And because Aaron, one of the few remaining people who doesn't use email or mobile phones, is also one of the few remaining people who just shows up at your door and says, "Let's go for a walk," the way people used to do last century and most of the centuries before that.

We crossed the campus and headed into the hills, the hills that would be mountains by English or East Coast standards, but are little more than an innocuous irruption in the tumultuous California landscape. It was a journey we'd made many times, occasionally together but most often separately. The first time I wandered up the Bancroft Steps and into the woods was sometime in 1968, a few years before Aaron was ready to start his own perambulations.

About halfway up the little road that dead-ends above Strawberry Canyon, there was always a steep, narrow set of stairs that led up to another street and, with its spectacular views of the city and the Bay, another dimension from the damp, musty, perennially shaded street we were on. But something was wrong: either we'd lost our minds, or the staircase was gone, replaced by a couple new condos. It couldn't be, could it? Nothing like that ever changes in Berkeley, especially not in the hills, which are a thing completely apart from the gritty, urban reality of the flatlands.

But yes, it had changed, yes, our stairway was gone, and so was our plan to get up above the trees before the last of the sunset colors faded away over the Golden Gate. It wasn't the end of the world; around the corner was a very different staircase, a broad stately one that I'd discovered back in 1970 when I was living in the Delta Kappa Epsilon house at Piedmont and Bancroft (long story; ask me some other time). Even then the stairs looked ancient, like some sort of Greek or Roman ruin, and 35 years had only enhanced their patina.

I'd sat there many times back in "the old days," even taken a picture to show the folks back East what a classy place Berkeley was. I'd like to show it to you here, but, well, it's buried somewhere and I don't have a scanner. Aaron and I sat there for about half an hour talking about what Berkeley had meant to us, how it had changed, how it would never change. Then I was off to El Cerrito to see the family and he disappeared into the night on a beautifully painted bicycle that Eggplant had apparently found in a creek. For a little while time had stopped and I remembered why I once loved this town so much.

On A Warm San Franciscan Night

I wandered through the Mission, down Market Street, up Powell past Union Square and over Nob Hill, then back down to BART by way of the Tenderloin. Because of the unusually warm weather, there were a lot more people than usual on the streets, though it still felt like a sleepy village compared with New York. To some people, that's a good thing, while I usually find it annoying, but on this particular night, I wasn't in the mood to be critical.

Maybe that's why the city also looked cleaner, safer, more inviting than it has in ages. It couldn't have changed that much in the six months or so since I was last here, could it? No, probably not, and even by warm November moonlight, it still compares unfavorably with New York, but for once I just didn't care and was glad to be right where I was.

It got me thinking: how much of my ranting and raving against San Francisco, against the Bay Area in general, is justified, and how much of it is simply a reflection of my personal tastes and prejudices? For years, for a couple decades, actually, I would have insisted that the SF Bay Area was beyond a doubt the best place on earth. Now I denounce it at the drop of a hat, and almost every time I visit manage to wind up in some neighborhood or situation that totally confirms all my worst opinions.

Walking up Bush Street, I saw some apartments for rent and caught myself thinking, "I could actually live here," which is probably the height of lunacy. I liked, always have liked, those old-fashioned San Francisco apartment buildings, and there are a few blocks on Bush that feel genuinely urban, sort of like New York's Upper West Side. But once the weather turned cold and I'd walked up and down the street a few times, I'd go completely bonkers. Small town life is not for me.

One thing that hasn't changed: between the St. Francis Hotel and Powell Street BART (about five blocks, for you auslanders), I was asked for money by 15 different people. Add to that the 5 people around 24th and Mission, and if I'd given each one a dollar, I'd be out an extra 20 bucks for my brief night on the town. And that's not counting the two New York-style beggars (regular subway riders will know what I'm talking about) on BART. First was a woman who announced to everyone that she had multiple sclerosis and needed X number of dollars to get to the hospital for her treatment. Then a young guy came into the car with a similar story: "I've just come from San Francisco General and they're sending me to Alta Bates (hospital in Berkeley) to have this burn (rolling up his pant leg to show everyone) looked at, and I don't have enough money to get off the train." (No explanation about how he got on the train, or why San Francisco's biggest hospital would send him to a smaller East Bay hospital at 11:00 at night.)

Everyone ignored him, and I did as well, burying my nose in my book, feeling ashamed of myself even though I was pretty sure it had to be a scam. He got more intense in his pleading, and then suddenly broke into tears. After a minute or two of sobbing still failed to produce any results, he snapped, "You fucking people need to grow up," and stalked into the next car to try again.

The thing was, his tears sounded real, even if his story didn't. And I hated myself for not just handing him a couple bucks; after all, I'd spent more than that just on coffee. But what I hated even more was the way that begging has become such an everyday part of life that most of us no longer see the beggars as individuals instead of as a pervasive urban nuisance. It's true that most beggars have alcohol or drug problems and that you're not doing them any favors by giving them money, but in order to cope with the constant hassle, I fear that we end up turning off part of our own humanity.

15 November 2005

Shopping Cart City

My feelings about the numerous people living out of shopping carts here in Berkeley have shifted over the years. Originally I was broadly sympathetic, as I think most Berkeleyans were. Besides, this was back in the 1980s, I was still smoking pot, and eagerly looking for any tangible evidence that Reagan was destroying society and forcing millions of decent Americans into poverty. The sad characters trundling up and down Shattuck Avenue with all their earthly possessions in a stolen shopping cart were our version of Depression-era soup lines: visible proof that capitalism had failed and that the End Times were near.

Since then we've had two Bushes and a Clinton, the economy has gone up, down and sideways, and the number of shopping cart people is, if anything, greater than ever. And as the shopping cart life has become institutionalized, some of the more successful denizens of the street are no longer satisfied with one shopping cart; today I saw a guy huffing and puffing as he dragged a wired-together train of five carts up Hearst Avenue, his possessions and scavenged treasures neatly divided and categorized among them.

I first began losing sympathy for the shopping cart people after I spotted a couple of them methodically stripping wheels off bicycles that had unwisely been left parked overnight in downtown Berkeley. What sympathy I had left pretty much vanished when the front wheel disappeared from my own bike, parked right on my front porch. I remember being surprised at the time, because I'd always thought of the shopping cart people as gentle, lumbering victims, a bit untidy perhaps, but an essentially harmless part of the local scene, like the spare-changing punks and the time-warp hippies. Then it occurred to me, "Well, if they'd steal a $150 shopping cart, why wouldn't they steal a $75 bike wheel?"

I tried this idea out on a few bike-riding friends, only to find them absolutely appalled at my heartlessness. The gist of their reaction was that taking a shopping cart from a local market wasn't stealing. "Safeway can afford a few shopping carts," they'd say. "So," I'd ask, "if some homeless person needs a bicycle, does that mean he's entitled to take yours?"

"That's different," they'd bellow, as if I was being deliberately obtuse. And perhaps I was. I'd certainly lived in Berkeley long enough to be familiar with the idea that people, especially "the poor," are entitled to take whatever they can get from "the rich," and, especially, "the corporations." To be perfectly honest, I'd subscribed to this theory myself for many years. It was only when I began questioning the terms that I ran into trouble.

Who, exactly, qualified as "poor," and therefore entitled to free stuff? Conversely, how "rich" did someone have to be before they abdicated their right to own property? At what precise point did a business change from being a "locally owned mom and pop" operation worthy of our sympathy and support into a blood-sucking predatory corporation that deserved to be looted into oblivion?

Unfortunately, these are not the sort of questions you want to ask around Berkeley, unless you're looking to be vilified as a right-wing Republican hater of the poor and oppressed, or at best, as someone who just likes to stir up pointless arguments. "Why do you even need to ask?" friends would say. "It's perfectly obvious who's rich and who's poor. You're just engaging in intellectual nitpicking."

Well, no, it wasn't perfectly obvious, and it's still not. And of course relativity comes into it: street beggars in downtown Berkeley are fabulously rich compared with millions of people trying to scrape out some sort of sustenance in sub-Saharan Africa, and horrendously poor compared with even the average working-class student or laborer in Berkeley. The inequities of the world are as myriad as the proposed solutions to them.

I've come to believe that the whole shopping cart/street begging/homelessness issue is not mainly one of economics. There are exceptions, no doubt, but it's my observation that the majority of Berkeley's street people are not living out of shopping carts because Bush has driven them to it, but because Berkeley has invited them to. That's not to say that there's something wonderfully attractive about living on the street - the relatively short time I spent being homeless easily disabused me of that notion - but that if it's accepted as a legitimate, even natural way of life, a certain number of people will decide, "Hey, it beats paying rent." Especially if those people have drug, alcohol or mental illness issues that make it difficult or impossible for them to maintain a "normal" life indoors.

The thing that really kills me is how Berkeleyans love to flatter themselves about how great-hearted and broad-minded they are to tolerate the mini-Hoovervilles that spring up in the city's parks and downtown streets. No politician in his or her right mind would suggest that the police confiscate the hundreds of shopping carts being pushed around town and return them to their owners; once when somebody in San Francisco actually proposed this, Supervisors quickly countered that then the City would have to find money to buy new shopping carts for the homeless.

But to me, Berkeley's self-proclaimed "tolerance" is actually indicative of one of the nastiest streaks in the city's character: it's self-centered obliviousness. Berkeley spends more money per capita on services for the homeless than probably anywhere else in America, yet the only visible result seems to be an ever-increasing number of homeless people. If this were strictly a matter of economics, then the same thing would be happening in cities across America, but it's not. It's not even happening in other Bay Area communities. By offering just enough help to allow people to continue live on the streets but never escape them, Berkeley reminds me of those rich and oh-so-liberal parents who give their kids an allowance in lieu of actually caring for them, and then are surprised when the little darlings end up in jail or dead from an overdose.

I've seen too many hippie parents operate in a similar way: in the name of being "groovy" and "liberated," they exercised no discipline or control over their kids. "Kids need to be free," they'd argue, when what they really meant was, "Hey, I'm not about to give up partying to look after some boring brats." It might sound strange to compare grown-up street people to children in need of care and discipline, but if someone is incapable of caring for him or herself, that person is effectively a child. Does he or she deserve financial and other material help from society? Yes, undoubtedly. But by handing out minimal help and thinking that the job is done, by being afraid to be so un-groovy as to say, "No, it's not acceptable for you to live permanently on the sidewalk in the middle of downtown," Berkeley is ultimately being as heartless - if not more so - than those cities who simply sweep the homeless from the streets under threat of beatings or prison.

12 November 2005

New York and the (sort of) Return of The Potatomen

When did I last have a bad time in New York? It was probably way back in 1973 when I got my head bashed in by muggers and nearly bled to death on the sidewalk at E. 10th Street and 3rd Avenue.

There were probably a few other less than happy moments in the 80s and 90s, having more to do with ruffled feelings or business dealings gone wrong than life-threatening violence, but at the moment I can’t recall any specific details, so they couldn’t have been too awful. But of my 21st Century New York adventures – and there have been a lot – every single one has been fabulous.

Not always in the same ways. Last summer, for example, the highlights were fairly prosaic, mostly hanging out with friends and baking in the 90-plus degree heat that enabled me to come back to dismal, grey London with a suntan that lasted into October. Topping up that tan was the last thing on my mind when I came back to celebrate my birthday (Oct. 28) and Halloween, especially when I arrived in the middle of the first real cold snap of the season, and spent the next three days wrapped up in my winter jacket trying to keep warm.

But it warmed up on Halloween, and kept getting warmer, so there I was, several days into November, sprawled out on the banks of the Hudson with a few thousand other sun-worshippers, getting nearly as brown as I was last August, even as the leaves changed color and drifted down around me every time the breeze stirred slightly. Because the sun, well on its way toward the winter solstice, hung so low in the sky, the river was one of the few places where you could escape the shadows that hung over most city streets, and even then, three or four hours of sunshine was the best you could hope to wring out of the day, but that only made it more precious, the way, like an unexpected revival of a nonetheless doomed love affair: you savor every last moment with similar measures of delight and desperation.

On my last full day in New York, a storm front blew up over Jersey City; at about 3:30 in the afternoon one of its advancing tendrils abruptly reached out in front of the sun. The darkness that descended was palpable, and as if the earth herself were shuddering, a chilly breeze rose up from somewhere and hundreds of thousands of leaves cascaded to the ground with a sigh of mass resignation. The sunbathers rose almost as one, dressed themselves, and walked off with a newfound sense of purpose toward what would soon be the canyons of winter. Day after day we had lain there in sun-kissed lethargy and dream-ridden indolence; in an instant it was gone, and, barring a miracle, would not return for what was already looking like a small eternity.

Never mind that; who goes to New York to sunbathe anyway? I did do a few other things besides flop around in the sun. On Oct. 26 I got to see Dr. Frank, doing a reading (and a musical performance) from his soon-to-be-published novel, King Dork. It’s about a preternaturally intelligent but socially dysfunctional teenager who spends or misspends (I can’t say for sure yet, since I’ve only read excerpts) his adolescence in an ongoing attempt to be in a rock and roll band. Because the kid is constantly writing songs for his bands to sing, Dr. Frank has the opportunity to put his own songwriting talents to work creating real-life versions of the songs, and in addition to reading a chapter called “The Lord Rocks In Mysterious Ways,” Frank sang four of them.

Three nights later, it was my own turn to do some singing. Astoria scenester Chadd Derkins had put together a eight-band punk rock cover show at Williamsburg bar The Charleston, and somehow I had gotten roped (well, they didn’t have to do too much roping) into being part of a band covering my own band, the Potatomen. It got even stranger when we recruited Michael Silverberg, a member of the last (or at least most recent) incarnation of the Potatomen, to play bass.

So essentially, half the Potatomen were in a band covering the Potatomen, if that makes sense. Never mind, it probably doesn’t, but we did it anyway. Along with Michael, three other New Yorkers, Oliver, Jesse and Grath, set about learning the songs before I arrived in town. Then we had time for one practice together, at which Oliver’s ex-girlfriend, Tina, who’d never even heard the Potatomen before, decided we needed a backup singer (and she was right). She took home a CD of the songs and learned them all overnight.

The show was on Saturday, the 29th of October, and try as I might not to be, I was a little nervous. It felt strange to be playing Potatomen songs without my genius guitarist and co-songwriter Patrick Hynes, and almost as strange to be on stage with a band again, for the first time in over four years. It shouldn’t matter, I kept telling myself; most of the bands had only had one or two practices to learn their songs, and one band, The Tattletales, hadn’t practiced at all, relying solely on singer-guitarist Christian’s musical ability to masterfully blast through a set of Kerplunk-era Green Day covers.

Chadd’s own band the Slaughterhouse 4, covered the Misfits, New Jersey’s Hot Cops did Screeching Weasel, and a hastily-thrown-together gaggle of glamorous girls went on as the So-So’s, doing more than ample justice to, of course, the Go-Go’s. For me that was the highlight of the night; it had the same excitement and energy as when I first saw the real Go-Go’s at the Mabuhay around 1979.

Other bands covered Andrew WK and NO FX, and by now you might be getting the same idea that I was getting as the night wore on: everyone else was covering famous bands, while we were getting ready to cover a band that half or more of the audience had never even heard of. Despite that, Chadd had decided to put us near the top of the bill, and as time for us to play approached, I began searching for reasons why we couldn’t. Minutes before we were supposed to go on, Michael still hadn’t arrived, so I figured I could use him as an excuse for canceling, but he strolled in just as our turn arrived, and so did my beautiful niece, comic artist Gabrielle Bell, so I reckoned I’d have to go through with it.

Well, it wasn’t so bad at all. We didn’t have as big an audience as some of the other bands, but the audience we did have was really into it, and even if there’d been no audience at all, it was an incredible feeling to be on stage and singing those songs again. The band played almost perfectly, and despite the PA system being atrocious and the drums falling apart mid-set, I had a ball. Because we hadn’t had time to learn more than half a dozen Potatomen songs, we augmented our set with a ferocious cover of Screeching Weasel’s “What We Hate” and The Smiths’ “There Is A Light That Never Goes Out,” which of course was also a Potatomen cover back in the day. The only thing missing from our set was NWA’s “Gangsta,” which we’d rehearsed but which Michael had effectively nixed by saying, “You can play it if you want, but you won’t have a bass player.”

Jonnie Whoa Oh, of Whoa Oh Records, took many, many pictures, all 238 of which can be seen here. The Faux-tatomen are about midway through the slideshow.

Anyway, enough about New York and the Potatomen; it all seems so very long ago now that I’m on the other side of the country, in a semi-warm and semi-sunny Berkeley. My second day here, I got to see Dr. Frank again, playing a solo show at the Bottom of the Hill, along with Kevin Army (producer of many of the early Lookout Records classics, who’s been doing a singer-songwriter thing for a few years now, and Specs, an acoustic drum and guitar duo featuring Jym, longtime drummer for MTX.

There’s lots more I could say about Berkeley, but for now I’ll confine myself to mentioning the homeless guy pushing a shopping cart adorned with an American flag and a “Viva Bush” sign. The first time I saw him, I figured it was supposed to be ironic, but this morning I saw him again, shouting at a bunch of other homeless guys: “If it wasn’t for the liberals, you bums wouldn’t be allowed to walk the streets!”